Marc Kilchenmann doesn’t like to repeat himself, what he appreciates is delving deeper when he takes on a subject. For his piece Murhabala, he focussed the women’s struggle for freedom in Iran. In the musical form, overtone and undertone structures meet and clash, sometimes harmoniously, sometimes in dissonant frictions.

A portrait by Friederike Kenneweg

Friederike Kenneweg

“I don’t know exactly why, but Persia, Iran – fascinates me since I’ve been a child,” says Marc Kilchenmann. “It has also stayed very present in my life later on. I learnt a bit of Persian, watched a lot of Iranian films and read Iranian poetry. What I particularly like is the language. It is said to be the most metaphor-rich language in the world.”

When Kilchenmann finds something that he is not yet familiar with, he is delighted. This was also the case when analysing US composer Ben Johnston’s string quartets, on which he wrote his doctoral thesis. “With Johnston, I once counted fifteen different third intervals. It felt like the ground was being pulled out from under my feet. That’s great. I said to myself: I don’t know anything. Fantastic!”

Maths and music, Iran and Ben Johnston

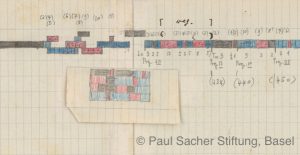

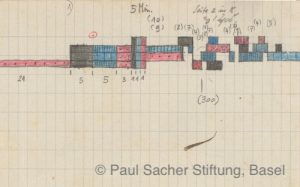

These two areas of interest meet in his work Murhabala for the microtonal keyboard instrument rhesutron and string quartet. Marc Kilchenmann discovered a mathematical treatise on binomial coefficients from the 11th century Persian polymath Omar Chayyām. He uses this, as well as the harmonic concept of Utonality and Otonality by composer Harry Partch, who had a significant influence on Ben Johnston, to find his musical structure. The term ‘otonal’ refers to intervals that can be formed using the overtone series, while those that are formed with the undertone series are called ‘utonal’.

The Persian word Murhabala means “juxtaposition”. In his piece, Marc Kilchenmann juxtaposes utonal and otonal interval structures. The string quartet, which mainly plays sustained ground notes, only moves in the otonal harmonic space. The rhesutron plays ornamental lines and uses both otonal and utonal intervals. As the piece progresses, the harmonic structure becomes increasingly complex. When the overtone series is combined with the undertone series, perfectly pure-sounding intervals are in some cases created. Mostly, however, tones meet at a distance that lies outside the traditional tonal system.

Murhabala for Rhesutron and string quartet, Recording 23.9.2024 in the Kantonsschule Küsnacht. Dominik Blum and Quatuor Bozzini

Waves like revolutionary movements

“You can listen to my piece in a very linear way, but you can also pay close attention to the harmony, you can just follow the string instruments or simply let your mind wander,” says Marc Kilchenmann. One thought that occupied him while composing were the women in Iran, who are constantly fighting against oppression and for their freedom. The harmonic connections that result from the structure of Murhabala resemble wave structures that are reminiscent of the ups and downs of protest being defeated and then re-strengthened. Marc Kilchenmann would like to emphasise this aspect even more clearly in the next version. “The waves that I actually imagined, this perseverance, this coming back again and again, that’s something that I don’t hear enough of in the piece. I’m going to emphasise that even more.”

The unfamiliar and the unknown

As intensively as Marc Kilchenmann has now explored overtones and undertones, his next composition will probably be about something completely different. After all, it is the unknown that appeals to him time and time again. “I would like to study something completely different again. I probably won’t do that now, because time is also finite. But I like dealing with completely different things and experiencing this unfamiliarity again: That’s a nicer state than knowing everything already. What could one expect from life then?”

Friederike Kenneweg

Omar Chayyām, Ben Johnston, Harry Partch, Quatuor Bozzini

neo-profile

Marc Kilchenmann, Dominik Blum, Kunstraum Walcheturm