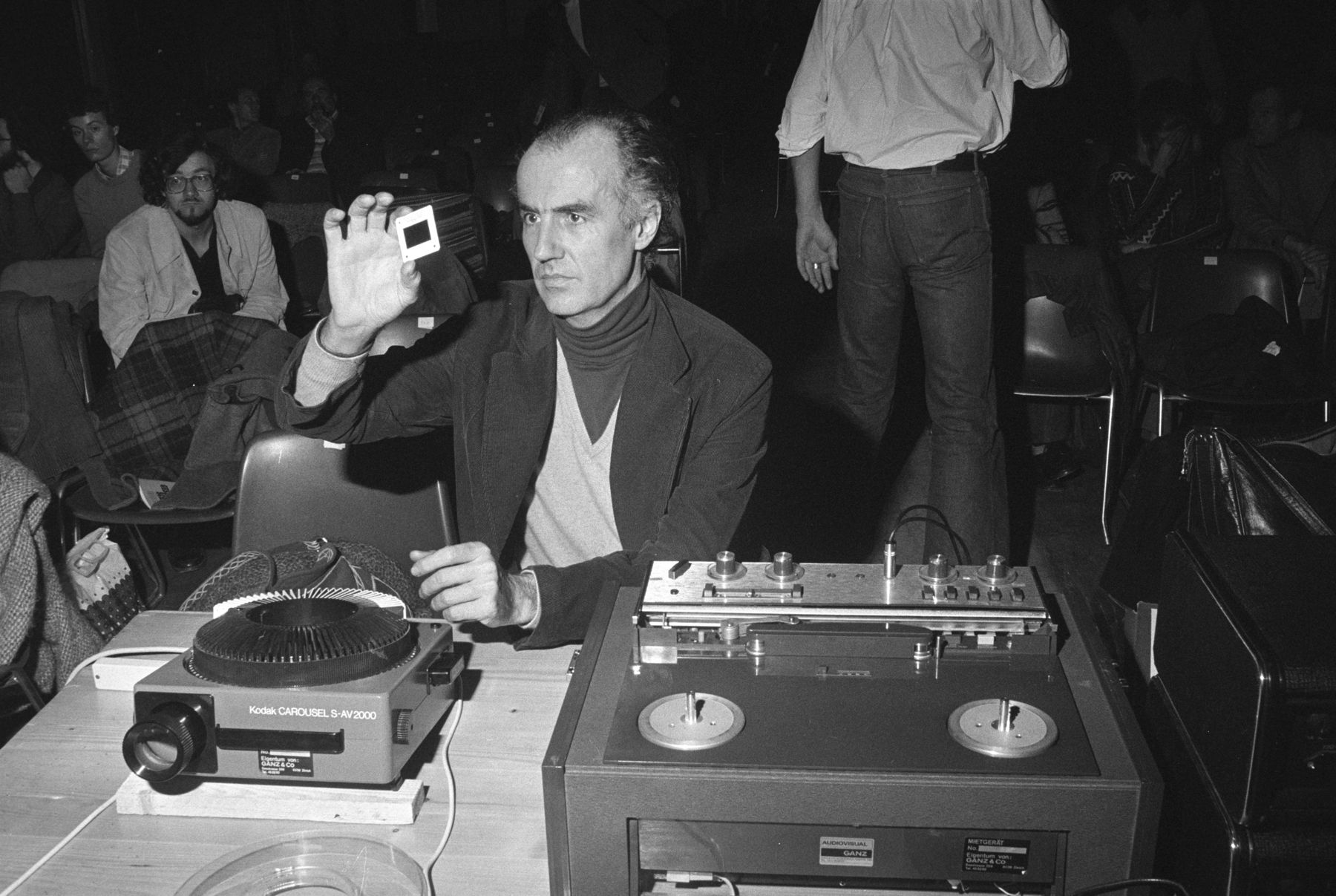

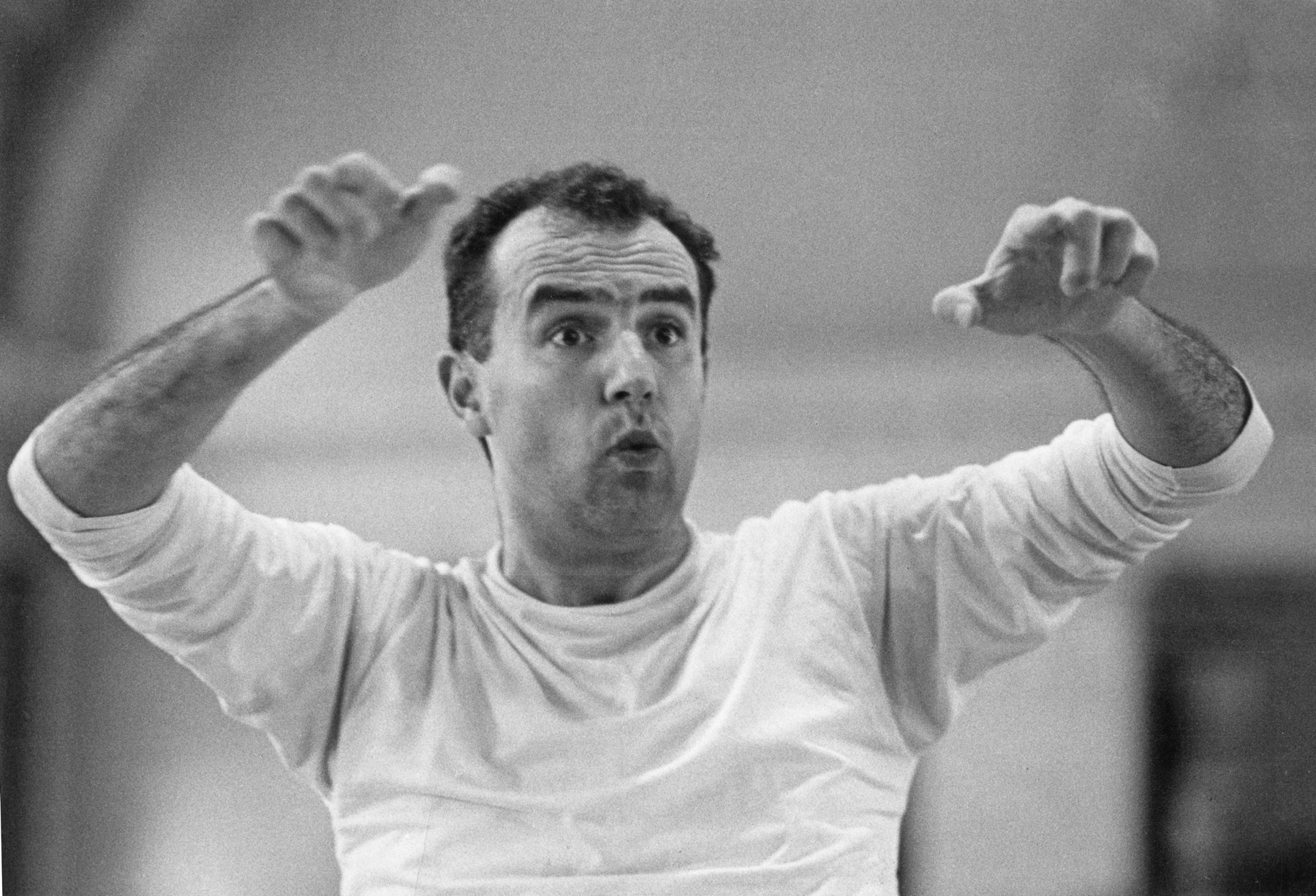

Celebrating the 100th birthday of composer Luigi Nono.

Luigi Nono (1924-1990) is considered a central figure of the musicalal avant-garde. A portrait by Florian Hauser on his 100th birthday, January 29, 2024.

Florian Hauser

They all turned up, every single one of them. Several thousand workers gathered during their break in order to hear what Luigi Nono has created on the basis of their sounds and noises. He had recorded the blaringly loud roars and hisses of the blast furnace of their steel factory and was now presenting his tape collage to them. Afterwards, the workers discussed it and began to ponder about their working conditions. ‘La fabbrica illuminata’ is the name of the piece that Luigi Nono dedicated to the steel workers in Genoa in the mid-1960s. A prime example of participation, one would say today. Ultra-modern, even to this day. That has always been Luigi Nono’s aim: he made music to create political awareness.

Luigi Nono was born into an educated Venetian middle-class household. When he was one year old, Benito Mussolini became the fascist dictator of Italy, which characterised Nono’s entire development, indeed his whole life. He wanted to fight against oppression, war and social injustice. The fact that he did is as a composer – he states – is only a coincidence, as he connected with the musical avant-garde after the Second World War.

It is a time of great change. A young generation of composers wanted to create a new musical world; the old expressions had had their day, clear structures were needed, as well as new compositional techniques and tools such as electronics.

Darmstadt in Germany became an important centre of the new emerging avant-garde.

Luigi Nono, Incontri für 24 Instrumente, UA 1955, in house-production SRG/SSR.

In 1955 – Nono was already firmly involved in the Darmstadt Summer Courses – he wrote a musical love declaration to his future wife, Nuria, Arnold Schönberg’s daughter: ‘Incontri’ for 24 instruments, the encounter of independent musical structures. ‘Just as two independent beings, different from each other, meet and though their encounter cannot become unity, it is still a meeting, a togetherness, a symbiosis’. After the premiere in Darmstadt, Nuria Schönberg and Luigi Nono became engaged and married shortly afterwards.

Three composers become the central figures at Darmstadt’s so-called ‘International Summer Course for New Music’: the Frenchman Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, from Germany and Luigi Nono.

What initially began as a wonderful and intense artistic friendship soon changed and differences became apparent. Nono did not wish to make “l’art pour l’art”, like his colleagues. He wanted to get out of the ivory tower, onto the street, to the people. And set, for example, farewell letters from resistance fighters sentenced to death to music….

“The human, the political cannot be separated from music”

“The human, the political cannot be separated from music”, Luigi Nono used to say. He tried ever more urgently to put his finger on social grievances, using all musical means at his disposal: wild orchestral impulses, sounds on the verge of silence, collages, electronics or music that spreads throughout the room.

“To awaken the ears, eyes, human thinking, intelligence, the greatest possible inwardness’” these are the words Nono used to describe his eternal goal in 1983, ‘”to bear witness as a musician and a human being”.

Luigi Nono, No hay caminos, hay que caminar, UA 1987, in house-production SRG/SSR: Nono had read the phrase ‘Caminantes, no hay caminos, hay que caminar’ (Wanderer, there is no path, you just have to walk) on the wall of a monastery in Toledo. This became his last orchestral work and the title could almost stand as a motto for Nono’s entire compositional work. No hay caminos, hay que caminar. The dynamics and tempo are extremely restrained, with dramatic cracks in the sound emerging only for brief moments. Nono uses only the note G, with quarter-tone increases and decreases, i.e. seven notes at quarter-tone intervals in all octave ranges. The differences between pitches and timbres disappear; it is a magical game that radically rethinks the relationships between parameters.

His life, just as his music and music-making, is exhausting… and Nono was ultimately broken by his own demands. ‘I proceeded to self-destruction,’ he would say at the end and when he died in his mid-60s, he had to realise that even music cannot trigger revolutions.

What could be considered his legacy? His uncompromising attitude. His motto. Ascolta! Listen up!

Florian Hauser

broadcasts SRF Kultur:

Luigi Nono zum 100: Helmut Lachenmann und seine Erinnerungen an Luigi Nono, Musik unserer Zeit, 31.01.2024, editor Florian Hauser.

Er vertonte die Abschiedsbriefe von Widerstandskämpfern, online-Text srf.ch, 29.01.2024: author Florian Hauser.

Zum 100. Geburtstag: Luigi Nono: Fragmente – Stille. An Diotima, Diskothek, 29.01.2024, editor Annelis Berger

neo-profil:

Luigi Nono