A portrait by Cécile Olshausen:

At the age of seven, he forgot his mother tongue Igbo and learned Swiss German. In his music, composer Charles Uzor sets out on a journey back to his Nigerian childhood, to the “pounding and quivering nature” of the African tropics, to the distant voice of his mother. Cécile Olshausen visited Charles Uzor.

Cécile Olshausen

It’s raining as I get off the train in St. Gallen. My smartphone I supposed to show me the way to Charles Uzor’s flat, in the centre of St. Gallen, just a two-minute walk away. Nevertheless, I manage to get lost.

Detours have led me to Charles Uzor. Many years ago, we happened to sit next to each other during concert and we talked. Since then, I often heard his name and music, but we never met in person again.

As he opens the door I shake off a few raindrops and Charles Uzor welcomes me into his spacious city flat. My gaze falls on a grand piano, on shelves full of books and CDs, while in the kitchen a radiator ripples like a fountain. A parasol leans in a corner of the living room reminding me of summer, while outside a big Christmas star hangs over the small balcony.

We take a seat at the dining room table. And from the urban holiday lights outside his window, our conversation slowly moves into the life and sound of Charles Uzor, a biography in which so many paths cross.

Charles Uzor was born in Nigeria in 1961. A few years later, a brutal war for independence broke out in his home region of Biafra. At the age of seven, he escaped the horrors of war and found a new family in St. Gallen, where he went to school and graduated. His studies – first oboe, then composition – later took him to Rome, Bern, Zurich and London. Finally, he wrote his doctoral thesis on melody and inner time consciousness. Charles Uzor’s works are many and varied: operas, dance, orchestral and choral compositions, but also many pieces for different ensemble settings.

Through music, Charles Uzor connects with his past and his childhood in Nigeria.

Our chat is calm, a conversation that allows for silence. A silence that I also find in some of Charles Uzor’s pieces, in Nri/ mimicri (2015/2016) for Ondes Martenot, percussion ensemble and tape for example. It is not a linearly developing composition, but rather a soundscape through which one senses by listening attentively. It is as if you enter a tropical house and find yourself – as soon as you step over the threshold – in a completely different world. For Charles Uzor, Nri/ mimicri is an approach to his “African origins”, as he puts it, a piece in which one can perceive ” pounding and quivering of nature”. And it is a reference to his ancestors, the Nri, a legendary Nigerian tribe.

Charles Uzor, Nri/mimicri, Percussion Art Ensemble Bern, UA 2016, Production SRG/SSR

Charles Uzor belongs to the Igbo people and grew up in the south-east of Nigeria, in the Niger Delta, a region with tropical rainforest and many rivers. He spoke Igbo with his family. When he came to Switzerland at the age of seven, this language disappeared within a very short time. To this day, Charles Uzor is haunted by the fact that he could simply forget his mother tongue.

… traditional Igbo sayings spoken on tape….

Fortunate circumstances led to him finding his family again after the Biafra War. As a teenager and firmly anchored in his Swiss life, Charles Uzor decided to stay with his St. Gallen family. However, he has stayed in touch with his Nigerian mother, who now lives in the USA, ever since. And in his cycle Mothertongue (2018), you can hear her voice, speaking traditional Igbo sayings on tape.

Charles Uzor, Mothertongue Fire / mimicri for tape, Maria Christina Uzor, 2018

Uzor processes these recordings into a composition and thus connects sonically with a language he no longer understands, his mother tongue.

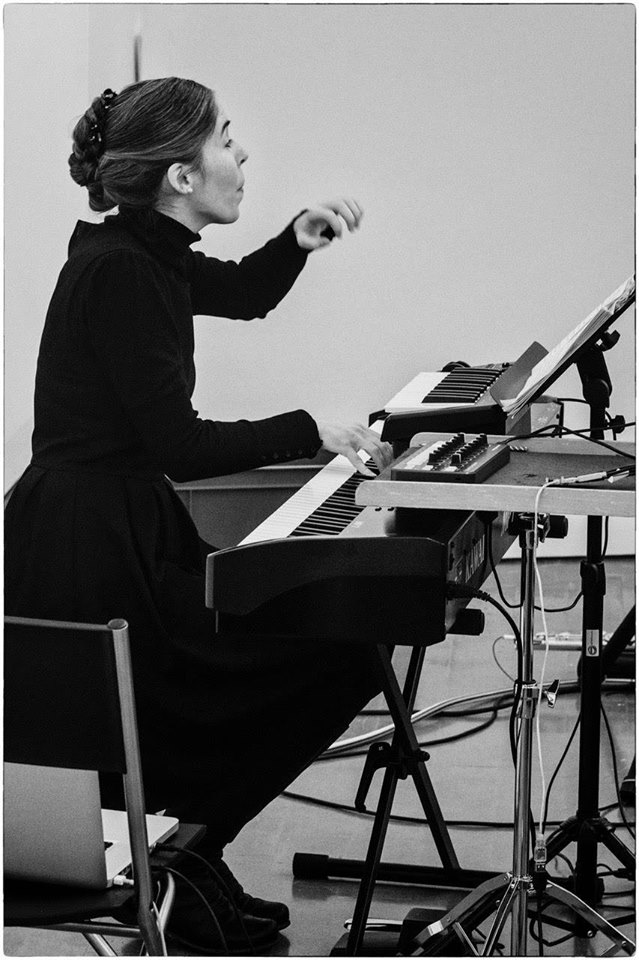

Charles Uzor, Mothertongue for Mezzosoprano, Ensemble and tape, Ensemble Mothertongue, world creation Musikfestival Bern 2020, Prodcution SRG/SSR

Charles Uzor’s compositional paths lead him not only back to the past of his African childhood, but also to centuries afar. During a short break in the conversation, when we open the windows to les some fresh air in, I take a look at Charles Uzor’s bursting, colourful CD shelf – and notice a lot of music by Pérotin, Guillaume de Machaut, Johannes Ockeghem or Costanzo Festa. I’m curious to learn, where this love for early music comes from as soon as we continue our conversation.

According to Uzor, pre-baroque music opens up a vastness and wildness, an order and structure that magically attracts him: “I often have the feeling that I was there; images of myself as a Renaissance man come to me, that’s how close I relate to it”. This music with its rounds, rhythms and repetitions also has something African for Charles Uzor. Thus, early music and African language sounds come together in his compositions. Paths that meet, moments of encounter.

What his music manages to combine effortlessly, the old and the new, the African and the Swiss, cracks in his everyday life experience. Because as a black man, Charles Uzor is affected by racism – even in Switzerland. And, as he tells me, every day. Everyday racism.

8’46” – that’s how long George Floyd’s agony lasted

Charles Uzor could not remain silent when George Floyd was murdered. For the black US citizen who was violently killed by the police in May 2020 and whose murder triggered worldwide protest – along with the Black Lives Matter movement, Charles Uzor composed the piece 8’46” seconds – that’s how long George Floyd’s agony lasted when his breath was taken from him. The composition only consists of breathing sounds. For Charles Uzor it was a necessity to write this piece in order to process his own deep shock and to externalise it.

Charles Uzor, 8’46” – Floyd in memoriam, world creation Musikfestival Bern 2020, Prodcution SRG/SSR

Charles Uzor’s homage to George Floyd was premiered in Bern on September 4, 2020. I have an intense memory of this focused performance by the Mothertongue ensemble, directed by Rupert Huber. Not pathetic at any moment. And at the end of the 8’46” no applause – but concern, quietness and just silence.

The rain has stopped now and it’s dark outside. We talked for a long time. In the kitchen, Charles Uzor makes coffee and the soothing ripples of the radiator brings us back from the depths of our conversation to the present. Then I set off towards the station. Now I know the way.

Cécile Olshausen

Musikfestival Bern – Mothertongue, Rupert Huber, Percussion Art Ensemble Bern

Broadcast SRF 2 Kultur:

Musik unserer Zeit, Mittwoch, 16.12.20, 22h: Pochen und Beben – der Komponist Charles Uzor, Redaktion Cécile Olshausen.

Neo-Profile: Charles Uzor, Musikfestival Bern, Percussion Art Ensemble Bern