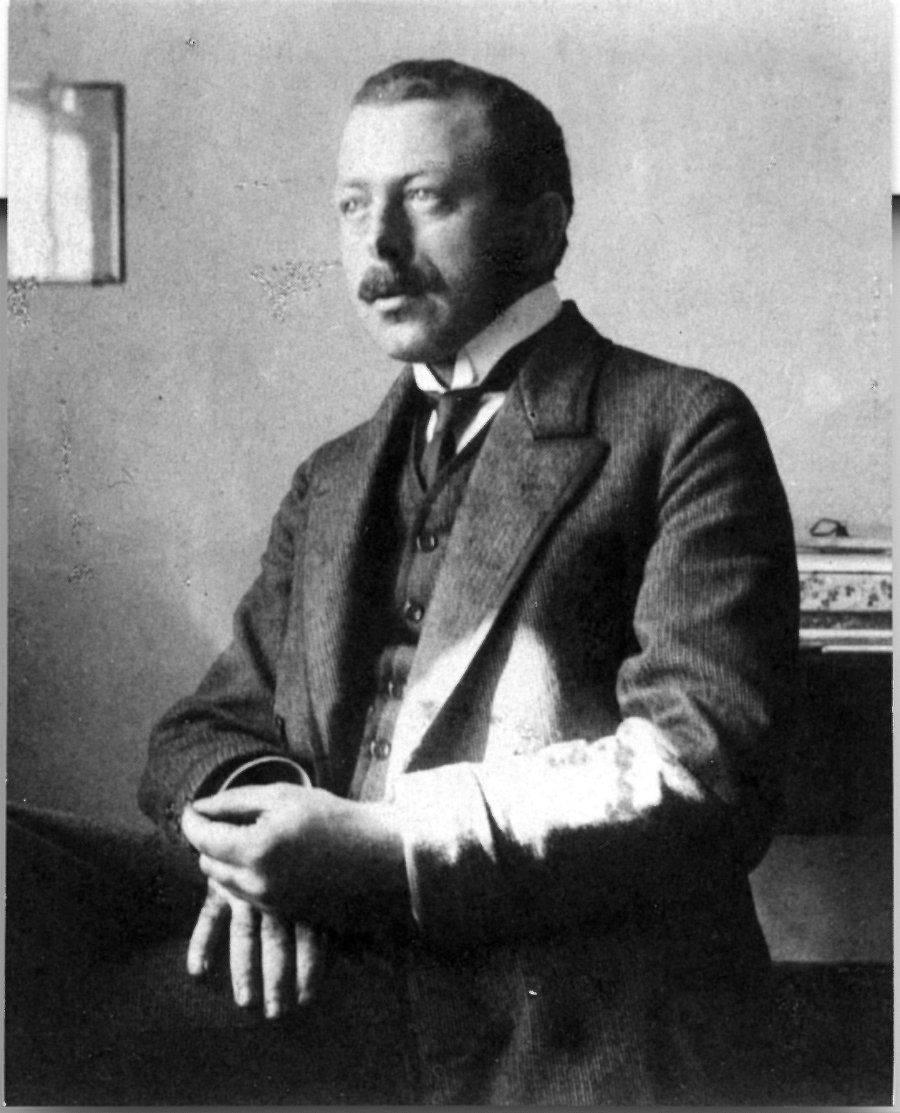

Hermann Meier (1906-2002) was a school teacher in the village of Zullwil in the so-called Schwarzbubenland and had five children to feed. Despite all this, he always found time to work on his unusual compositions – even if initially merely destined to sit on a shelf, as he experienced no major successes or performances during his lifetime. His legacy has been analysed by musicologist Michelle Ziegler.

An interview with Friederike Kenneweg.

Friederike Kenneweg

‘It all started when I first heard Hermann Meier’s during a concert back in 2011,’ recalls Michelle Ziegler, ‘I was immediately fascinated by it.’ Back then, Tamriko Kordzaia and Dominik Blum played Hermann Meier’s Thirteen Pieces for Two Pianos from 1959.

‘These are thirteen separate sections with very different characters. At that time, I was already working on the realisation of artistic ideas in music, and I found this to be consistently implemented here.’

The Thirteen Pieces for Two Pianos reveal the multifaceted nature of Hermann Meier’s music, which can be loud and direct, but also delicate and sometimes humorous. Tamriko Kordzaia, Dominik Blum, Concert 19th of May 2011, Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, produced by SRG/SSR.

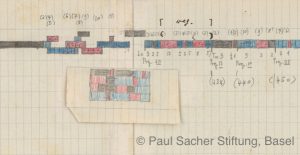

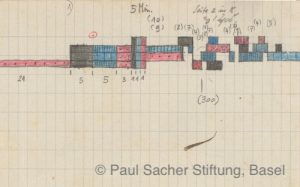

When Michelle Ziegler learned that the composer’s works were sitting largely unexplored at the Paul Sacher Foundation and that there all kinds of graphic plans were to be discovered there, she found her dissertation project. “That ended up being the focus of my project: Meier’s piano music and his pictorial notation.”

Notes in school notebooks

In order to be able to read Meier’s notes, Michelle Ziegler even learnt a special shorthand writing. The composer, who had unlimited access to exercise books as a primary school teacher, constantly recorded his thoughts in this form: on music, contemporary art and the progress of his work.

‘You could almost call him a graphomaniac,’ says Michelle Ziegler. The large number of exercise books, plans and sheet music that are now in the Paul Sacher Foundation could keep one busy for a lifetime.

At odds with his time’s music scene

The fact that, despite his constant productivity, Hermann Meier received little recognition during his lifetime is due to his unconventional compositional path. He had been studying twelve-tone music on his own since the 1930s and initially found a sympathetic teacher in Wladimir Vogel after the Second World War. However, he increasingly turned away from it, first finding an even more radical approach to serial composition and finally, inspired by the visual arts of Piet Mondrian and Hans Arp, moving on to work with sound surfaces. From 1955 onwards, Meier worked with graphic plans in which he visually sketched the structure that he later translated into musical notation.

His way of composing encountered little understanding at the time. Although endeavouredly searching for performance opportunities, he only received rejections, but nevertheless continued to compose unwaveringly, although only for the shelves.

Sound as canvas

Keyboard instruments play a central role in the Meier’s work, as he was himself a very good pianist. A work that Michelle Ziegler particularly appreciates is the 1958 piece for two pianos (Hermann Meier-Verzeichnis HMV 44).

“This is a stunning piece in my opinion. I can listen to it again and again and always hear different things.”

In the piece for two pianos HMV 44 written in 1958, here played by von Tamriko Kordzaia and Dominik Blum, Hermann Meier experimented with three structural elements dots, lines and areas.

Late recognition:Klangschichten’

The fact that Meier’s efforts to have his works performed did not bear fruit was also due to the fact that they were too difficult for the instrumentalists of the time. It is therefore not surprising that the composer turned to electronic music. In 1976, at the age of seventy, he indeed succeeded in realising his first work for tape, Klangschichten, in the SWF experimental studio – with which he was awarded a prize in December of the same year.

A new style in his later years

From 1984 onwards, pianist and composer Urs Peter Schneider took an interest in Hermann Meier’s music and premiered some of his works as part of the ‘Neue Horizonte Bern’ concert series.

Piano piece for Urs Peter Schneider, played by Gilles Grimaitre

With the late opportunity to see his instrumental pieces performed, Hermann Meier once again developed a new style. Michelle Ziegler discovers this, for example, in the Piano Piece for Urs Peter Schneider from 1987.

Concert HKB Bern 2017, SRG/SSR Eigenproduktion.

“The rhythm as well as the element of duration became very important. By then he was already over eighty and changed his composing considerably because he became even more fascinated by other aspects.”

In the meantime, Hermann Meier’s work has received a fair amount of attention. In 2018, his piece for large orchestra and piano four hands from 1965 was premiered at the Donaueschingen Music Festival. Michelle Ziegler particularly enjoys concerts like this. “It’s important to me that Hermann Meier’s music doesn’t just remain on paper, it should be heard.”

Friederike Kenneweg

The Paul Sacher Stiftung has organised and restored the composers archives and compiled a catalogue. Composer and bassoonist Marc Kilchenmann made the sheet music available as a facsimile edition published by aart Verlag.

Pianist Dominik Blum has recorded the complete works for piano solo by Hermann Meier from 1948 onwards.

Michelle Ziegler published the volume Musikalische Geometrie. Die bildlichen Modelle und Arbeitsmittel im Klavierwerk Hermann Meiers and, together with Heidy Zimmermann and Roman Brotbek, the catalogue for the exhibition Mondrian-Musik. Die graphischen Welten des Komponisten Hermann Meier.

Sendung SRF Kultur:

Kontext, 10.1.2018: Hermann Meier, ein lang verkannter Musikpionier, Autor Moritz Weber

neo-profile:

Hermann Meier, Urs Peter Schneider, Gilles Grimaître, Tamriko Kordzaia, Dominik Blum, Marc Kilchenmann