The “International Society for New Music” was founded 100 years ago, with the aim of creating network- as well as showcase-opportunities for contemporary music from all around the world. Its Swiss section, SGNM, was launched in Winterthur the same year. It organised six of the annual “World Music days” in 2004 and contemporary music even travelled through Switzerland by train.

A portrait by Thomas Meyer.

Thomas Meyer

31 years ago, in the church of Boswil, the ‘ensemble für neue musik zürich’ played an exciting programme, including works by Japanese composer Noriko Hisada and Australian composer Liza Lim. The two were not yet thirty years old and unknown in this country at the time – but they were not to remain so for long, as the ensemble was enthusiastic and gave them both several commissions over the decades. CDs were made and a long friendship developed. That concert is a beautiful example to me of what could happen at the so-called “World Music Days”.

Voodoo Child by Liza Lim (1990) – ensemble für neue musik zürich directed by Jürg Henneberger / Soprano: Sylvia Nopper, Kunsthaus Zürich 1997, © SRG/SSR

The festival took place in Zurich in 1991, gathering musicians from all over the world and on one afternoon the guests were taken to the idyllic Freiamt. These “World Music Days” thus fulfilled precisely the purpose of bringing new music from all countries together across oceans and continents, as stated by the festival’s organisers: the “International Society for Contemporary Music IGNM” or ISCM. The input came from the composers Rudolf Réti and Egon Wellesz. On 11 August 1922, an illustrious crowd met at the Café Bazar in Salzburg. Names like Béla Bartók, Paul Hindemith, Arthur Honegger, Zoltán Kodály, Darius Milhaud and Anton Webern were among those present; others had excused themselves.

The time were highly interesting, immediately after the world war had destroyed all order and nothing could be taken for granted any more. New music found itself in a changed culture. Exhausted by the war, but also by the violent scandals of 1913, it began to withdraw and organise itself. Schönberg and his circle in Vienna during the years 1918-21 with their “Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen”. Edgard Varèse founded the “International Composers’ Guild” in New York in 1921 with the aim of performing modern music. In the same year, the «Kammermusikaufführungen zur Förderung zeitgenössischer Tonkunst» were held for the first time in Donaueschingen. The name is significant, contemporary music had to do something and reform itself.

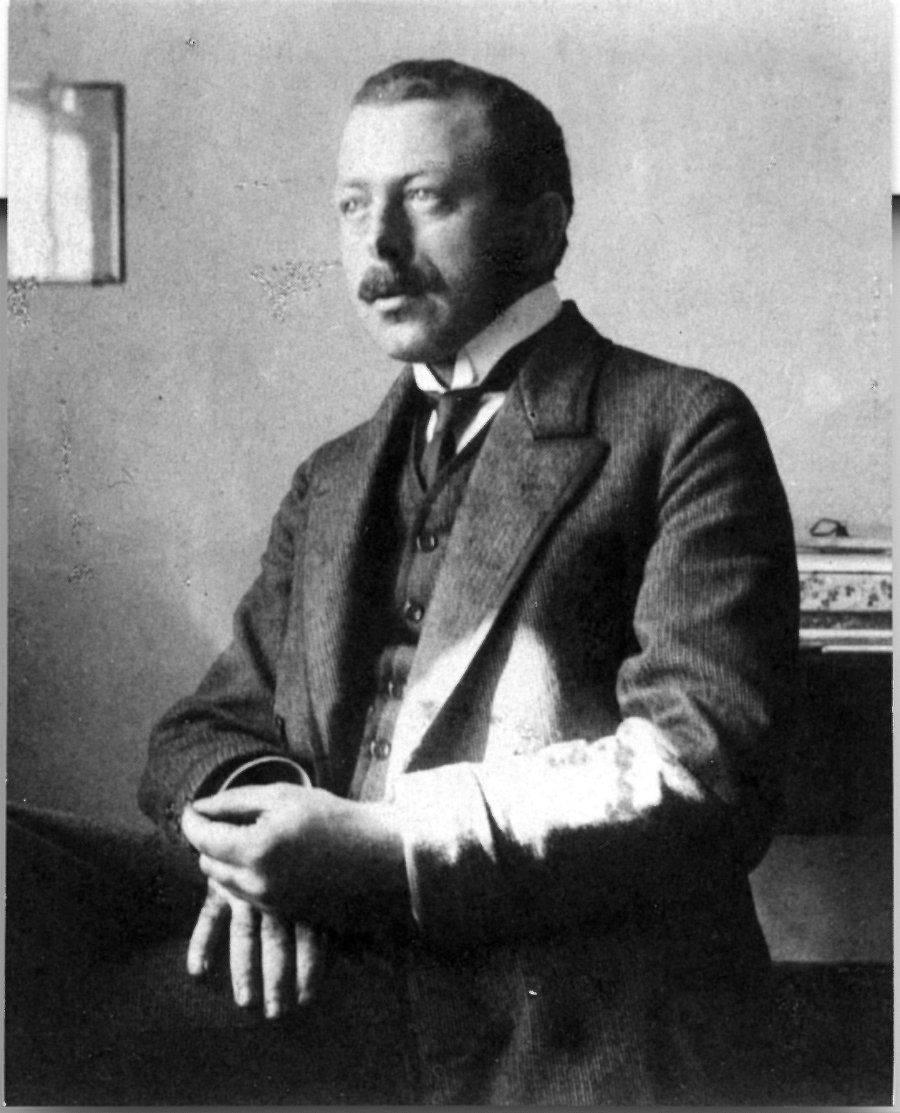

Richard Strauss was involved as president in IGNM’s founding, but soon handed the office over to English musicologist Edward Dent. Although the first impulse came from the Austrians, the British soon took over both leadership and administration. National sections came into being. As early as October, Werner Reinhart, a patron of the arts from Winterthur, Switzerland, came forward and announced a Swiss section. He had money and an interest in contemporary music, so the section took up residence at Rychenberg. In 1926, the World Music Days were held for the first time in Zurich, where, for example, Webern’s Five Orchestral Pieces op. 10 were premiered, followed by Geneva in 1929. The IGNM ship set sail and crossed the continents for its festivals.

World music festivals stand for communication and exchange between countries

The World Music Festivals are the heart of the organization, trying to do something in order to unite nations – even if only by approaches. “No music festival, no arts community would be able to prevent catastrophes like the one that broke out in 1914,” wrote Austrian music historian Paul Stefan after the Geneva festival. “But every bond has been tightened since then, and quite unlike in the past, the artists of today have become companions.” Admittedly, this degenerated into conflict again a few years later, when in 1934, on the initiative of Richard Strauss, a counter-organisation, the Nazi-affiliated “Permanent Council for the International Cooperation of Composers”, was set up to undermine the influence of the IGNM. In 1939, for example, Czechoslovak musicians were forbidden to travel to the World Music Festival in Warsaw.

All member countries propose compositions for the World Music Festivals, which are then evaluated by a jury on site and supplemented with programme ideas from local organisers. Fifty-fifty should be the ratio between the two parts. The programme is colourful and usually has no common denominator. But taking a look at the list of works, one can find many masterpieces. For example, Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron was premiered in Zurich in 1957. Some things might get lost or forgotten, but long and lasting connections are made, which is IGNM’s essence: communication and exchange between countries.

Gemini, Konzert für zwei Violinen und Orchester by Helena Winkelman, Premiere with Sinfonieorchester Basel and Ivor Bolton, violins: Patricia Kopatchinskaja / Helena Winkelman: the first woman to represent Switzerland at the World Music Days in Ljubljana in 2015, where her piece Bandes dessinées was premiered.

In 1970, the World Music Days took place in Basel, in 1991 in Zurich, and in 2004 the IGNM delegation travelled by train throughout Switzerland. This unusual idea under the title Trans-it was developed by a team around composer Mathias Steinauer, a completely new kind of impulse.

Steinschlag (1999) by Mathias Steinauer «World Music days» 2004 at Infocentro NEAT.

Those were the highlights, but in general the Swiss section, SGNM, is rather quiet and anchored in the local scene. The national society currently consists of eight regional groups. Several festivals and ensembles are also affiliated members, all organising concert series and often bringing unknown music to this country.

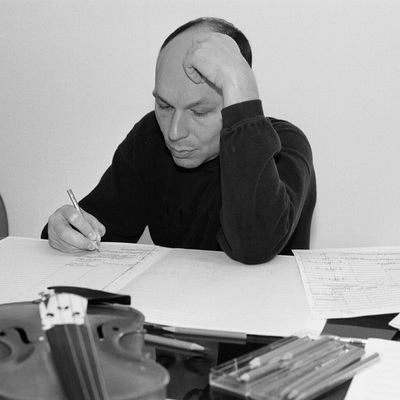

The national section has become significantly more active again in recent years however. Singer, performer and composer Javier Hagen has set some accents since taking over presidency in 2014.

First of all, this concerns historical examination, as some things had been handed down incorrectly and had to be corrected – which was especially important in view of the centenary. Valuable correspondence on the founding period was found in Winterthur. Documentation is necessary because much has been lost and difficult to find. Fortunately, former SGNM president, Zurich critic and organist Fritz Muggler, has a rich archive.

66 IGNM sections from 44 countries

The world music festivals are also documented. Not only the past, but also the present comes alive. Even if you were to travel to the festivals every year and listen to around 120 works each time, that would still make it impossible to get an overview of what is happening in all 66 sections from 44 countries. That is why the SGNM regularly presents music from all over the world in its “Collaborative Series” online.

For the jubilee, the Swiss organised a choral competition in four categories together with the Basques, Latvians and Estonians – a sign that SGNM wants to open up to other circles. 108 compositions from 78 countries arrived, with Luc Goedert from Luxembourg and Cyrill Schürch from Switzerland winning the first prize aequo.

Cyrill Schürch, Nihil est toto – Metamorphosen for choir a capella, premiere with the Zürcher Sing-Akademie and Florian Helgath, Zurich 2018, inhouse-production SRG/SSR.

There has also been an opening inside the head association, ISCM. At Javier Hagen’s suggestion, the number of official ISCM languages – so far German, English and French – has been expanded to include Arabic, Chinese, Russian and Spanish. The world is opening up – and music with it. A sign of this is that next year the IGNM will meet for the first time in South Africa, in Johannesburg/Soweto.

Thomas Meyer

Read more about the association’s first six decades, in the exhaustive volume IGNM – The International Society for New Music by Swiss musicologist Anton Haefeli.

The SGNM homepage features many tracks as well as visuals documents.

SGNM is also committed to Swiss Music Edition (distribution of musical scores) and musinfo database, two important tools for local music and its distribution.

neo-profiles:

ISCM Switzerland, Javier Hagen, Mathias Steinauer, Helena Winkelman, Liza Lim, ensemble für neue musik zürich, Cyrill Schürch, Patricia Kopatchinskaja