Merlin Züllig, alias Merlin Modulaw, describes himself as a ‘sonic architect’. Born in Zurich and now based in Paris, he studied composition and sound design in Switzerland and explores new artistic spaces with his combinations of acousmatics, 3D sound, sound design and pop references.

Friedemann Dupelius

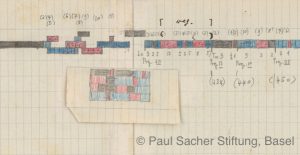

‘Decorating a table is composing, a bouquet of flowers is a composition. To me, the term composition is very broad and sound design is a part of it’. Merlin Züllig, alias Merlin Modulaw, thinks a lot in terms of connections and associations. There is hardly a musical genre or creative activity that he does not see in connection with one another, which is something that became apparent from very early on in his biography, Merlin Modulaw is not yet 30 and belongs to a generation that socialised on online music platforms such as Soundcloud in the 2010s. This was where musicians (often from their teenage bedrooms) shared their tracks with the world without the help of record labels or distributors. Inspired by hip-hop production and electronic club music, Modulaw deepened his skills in composition and sound art by studying at the music academies of Basel and Bern. There he came in touch with contemporary and acousmatic music, music for loudspeakers without visible instruments, and immersed himself in the subject of 3D audio.

Sounds for spaces: The „Sonic Architect“

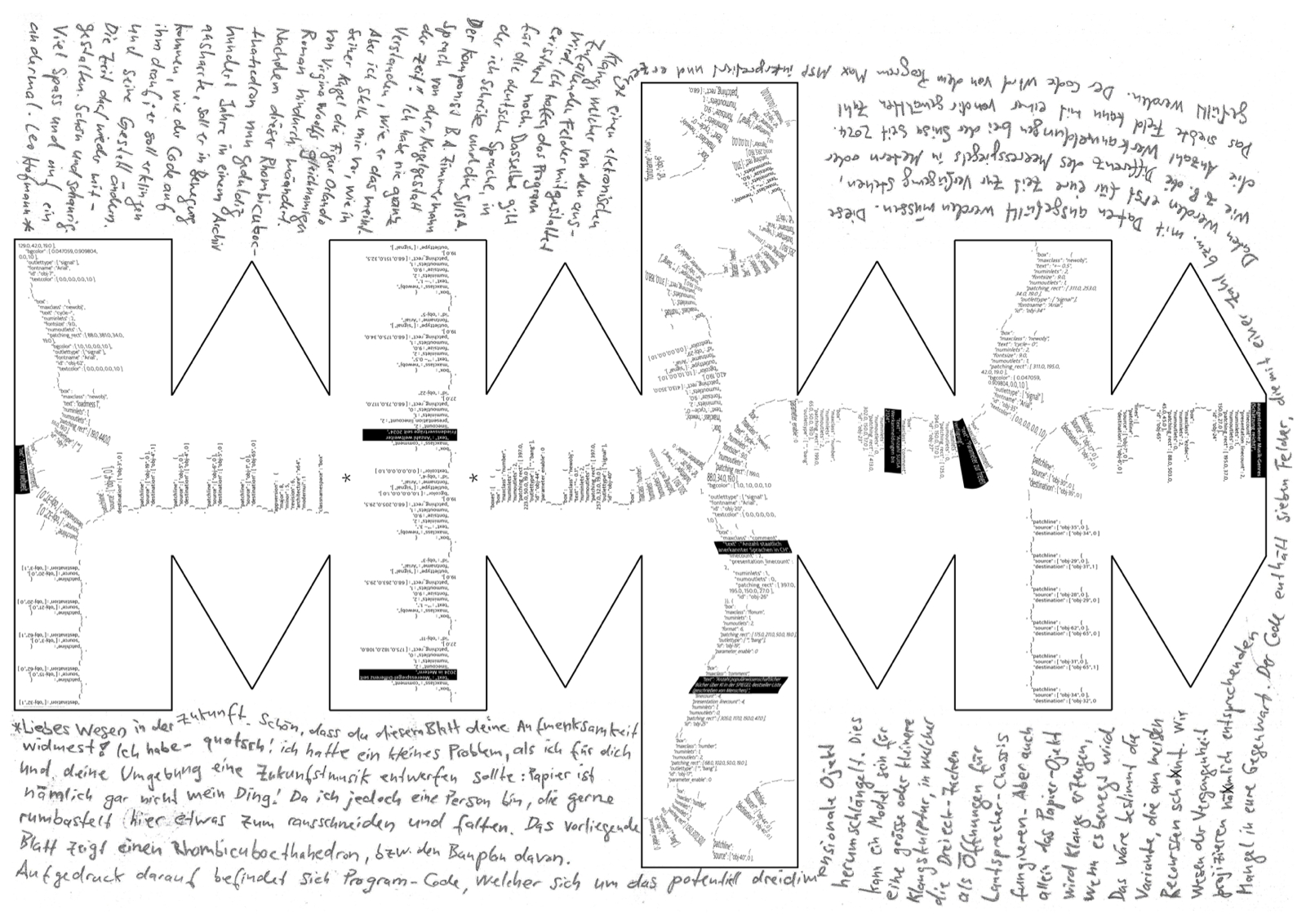

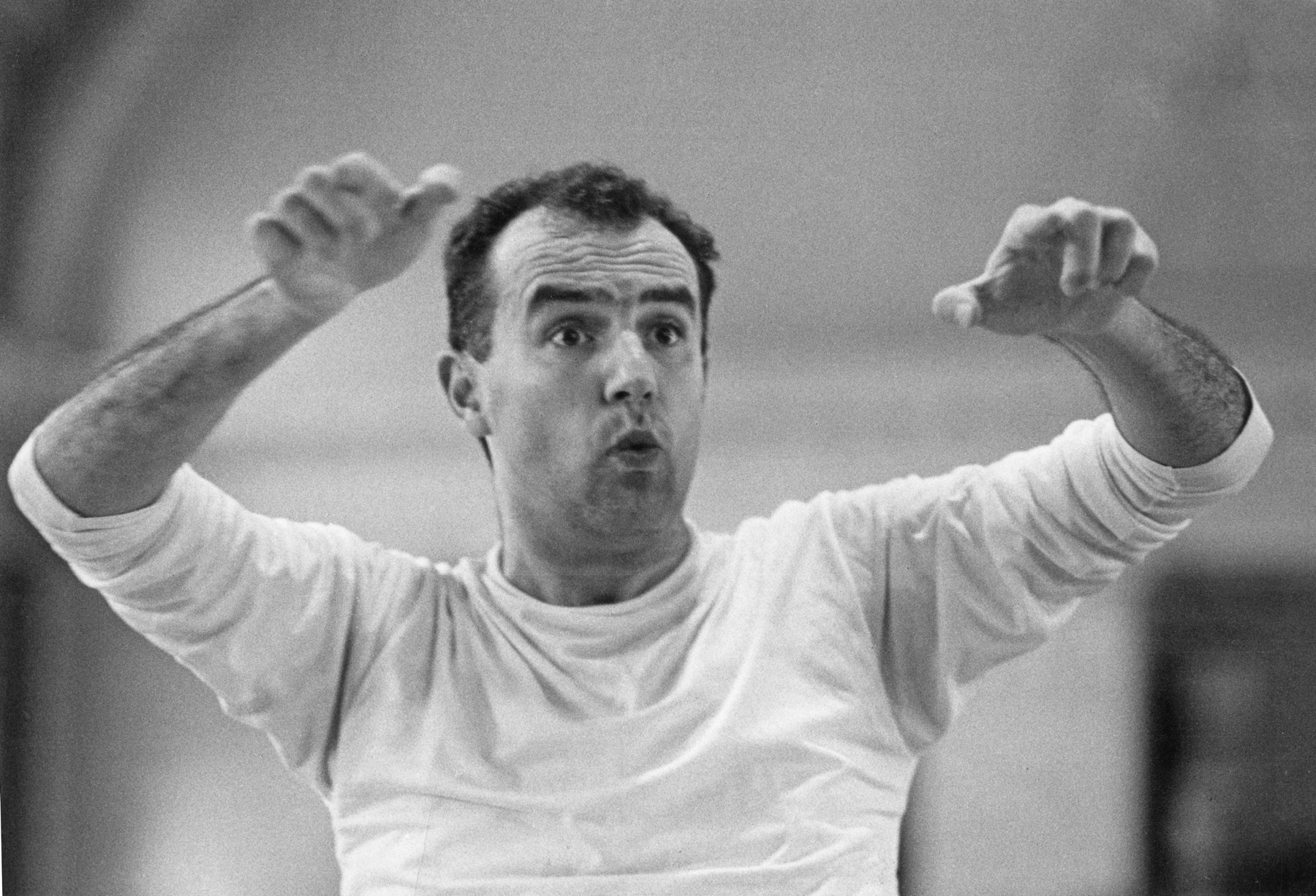

This is how the self-definition ‘Sonic Architect’ came about, as the terms musician, composer, producer, sound artist or sound designer were not enough for Merlin Modulaw to describe the broad bouquet from which his activities are composed. ‘Sonic Architect’ means, on the one hand, designing sounds and music for specific spaces, such as in the concert series “Spectres”, which Modulaw organises together with Axel Kolb in Zurich. Here, composers open up a wide variety of spaces with loudspeaker constellations – from large industrial halls to cellar vaults and art galleries.

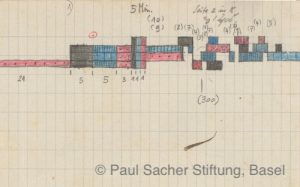

Merlin Modulaw’s acousmatic compositions combine field recordings and synthesiser sounds, taking the listener to various imaginary places

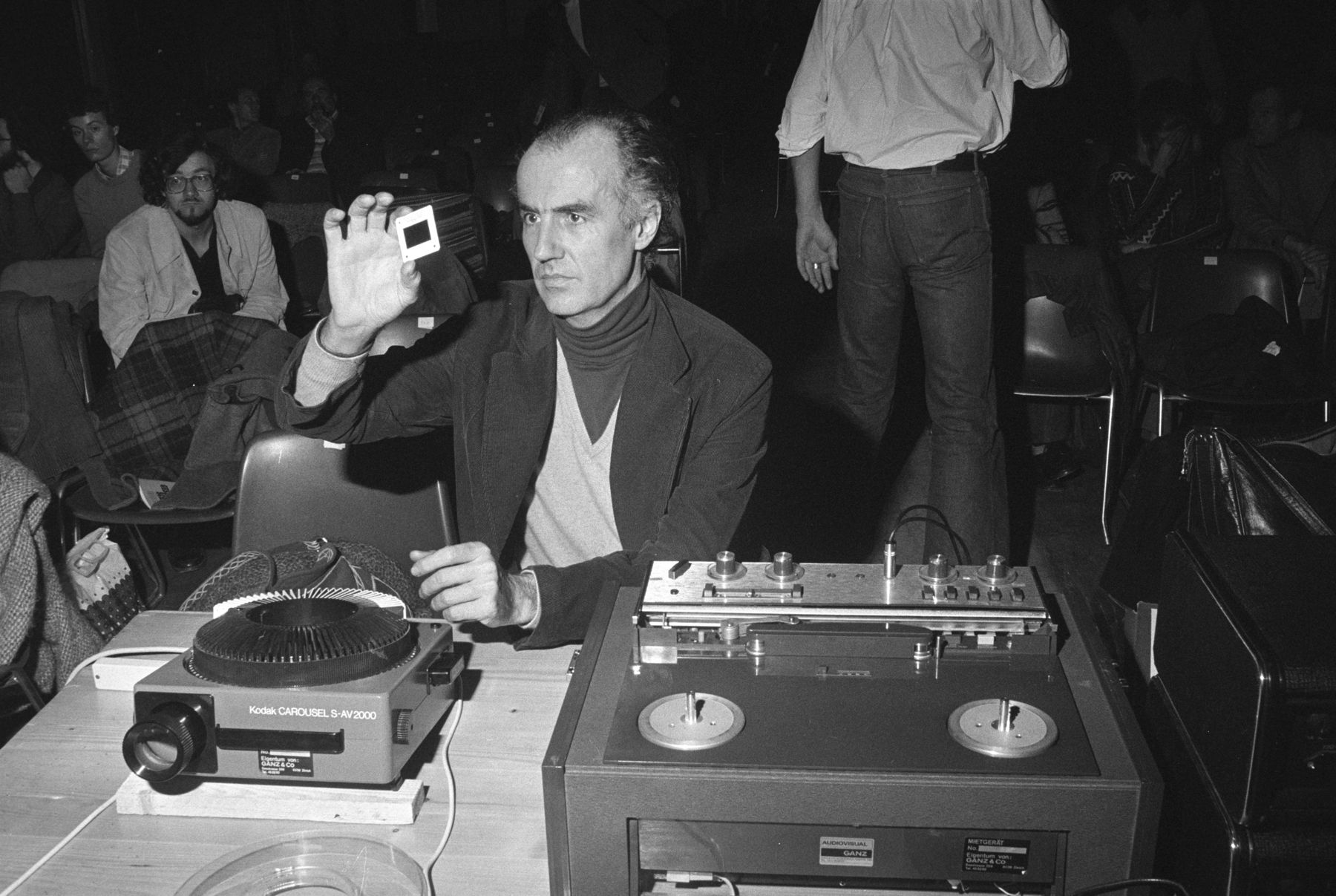

Depending on both location and artistic intention, the loudspeakers are set up in a circle, directed frontally towards the audience or sometimes fill the walls and corners of the room with electronic-acoustic compositions that are specially mixed and staged for the specific rooms with their natural frequencies and reverberation times. The participating composers rotate from edition to edition. In December 2023, the ‘Spectres’ series was part of the Zurich Sonic Matter Festival. At the ‘Biennale Son’ in autumn 2023 in Valais, Merlin Modulaw spatialised the sound traces of other artists in an installation by Deborah Joyce-Holman, distributing the sound material across five loudspeakers set up in a row and on subwoofers under a bench for the audience. For him, this is also a compositional act in itself, even if he did not create the sounds himself.

But ‘Sonic Architect’ means even more to Merlin Modulaw: the sounds do not only create architecture, but also identities – they capture something specific from the indeterminate sound stream of the present and make it accessible. This can be applied to all of Merlin Modulaw’s musical activites, including his work as a mastering engineer, for example, when he gives other artists’ music the delicate polish that sets the scene for both their identity and his own – or as a sound designer who uses sounds to give movies or advertising clips their own atmosphere and identity.

‘I’m often annoyed by films with a distinctive soundtrack that is simply slapped on and tells you what emotions you have to feel. So I try to incorporate the musical information at the level of sound design and emotionally, i.e. directly in the scene. For example, a wind in the background might contain a minor chord that nobody consciously perceives as such, but which subtly colours the surroundings and creates a certain aura.’Merlin Modulaw created the sound design of an image video for the Zurich design brand Casella Meyer with his typical sound language

Sounds for voices: The Associator

The musical outcome resulting from this approach and workflow have made other artists curious to collaborate with Merlin Modulaw. It is often vocalists – singing, rapping, experimenting with their voice or with effects such as autotune – who want to clothe their voice in Modulaw’s sound. Nine of them found a place on the album Ignition, released in 2023. Merlin Modulaw’s work with vocalists is also very much about associations: ‘to me, the voice is a reference point that listeners can quickly orientate themselves by. I can then combine vocal elements that are often associated with pop music in the broadest sense with references from contemporary or electro-acoustic music and thus introduce experimental music to a different audience.’

The track ‘C’ is part of the album ‘Ignition’ and was created in collaboration with Californian rapper DÆMON.

These combinations of references – alongside technical innovations – are the means by which innovation takes place in Merlin Modulaw’s music. As a border crosser between the familiar and the yet-unknown, Merlin Modulaw has opened up several new spaces in recent years.

Friedemann Dupelius

Merlin Modulaw, Merlin Modulaw auf Bandcamp, Merlin Modulaw – Ignition (Album), Konzertreihe Spectres in Zürich, Deborah Joyce-Holman, Axel Kolb

neo-Profiles:

Merlin Modulaw, Festival Sonic Matter