At Donaueschingen Music Festival 2023, ensemble Ascolta will premiere “Dunst – als käme alles zurück” by Elnaz Seyedi, commissioned by the ensemble in tandem with author Anja Kampmann.

Elnaz Seyedi’s portrait by Friederike Kenneweg.

Friederike Kenneweg

For Elnaz Seyedi, composing always means collaboration. Born in Tehran in 1982, she studied, among others, with Younghi Pagh-Paan in Germany and Caspar Johannes Walter at the Hochschule für Musik Basel and draws a lot of energy from the very different encounters and constellations that her work entails. Dunst – als käme alles zurück is Seyedi’s second collaboration with Ensemble Ascolta.

“That’s an advantage because the musicians know what they can expect from me and thus engage with my work in a different way.”

Happiness in search of sounds

This led to special moments of happiness during the preliminary rehearsals for Seyedi’s Donaueschingen debut, when she searched for the right sounds for the piece in individual rehearsals with the ensemble’s musicians. For example with percussionist Boris Müller.

“He kept pulling out more things like shells and stones and in the end the whole room looked as if it had been full of children playing for eight hours. I went home with material for three pieces. It’s just the most beautiful thing and gives me a lot of energy.”

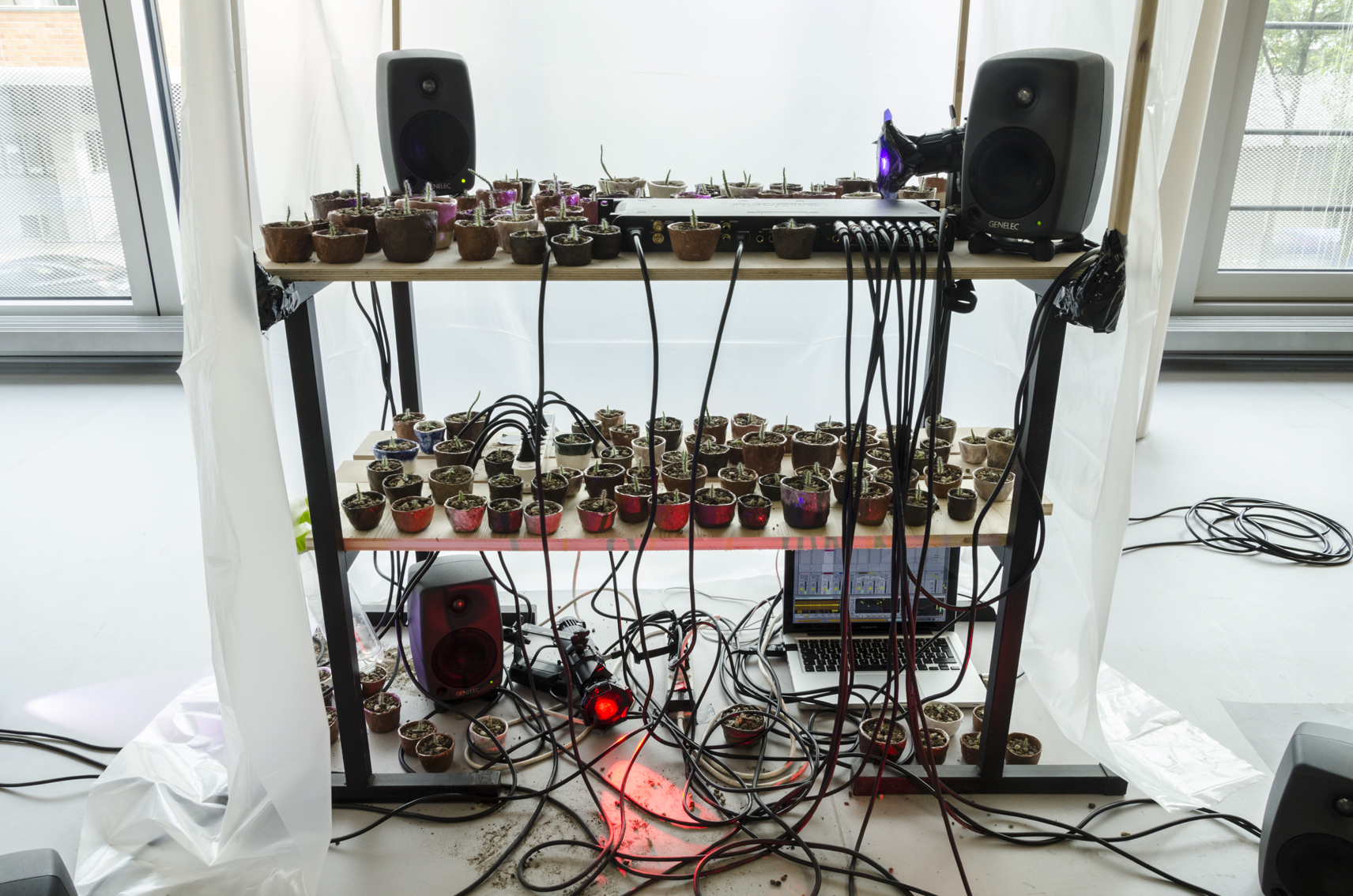

Glasfluss is another of Elnaz Seyedi’s works that emerged from a close collaboration, in this case with percussionist Vanessa Porter in 2022.

Taking the risk of composing together

Elnaz Seyedi has a special kind of collaboration with composer Ehsan Khatibi, who also comes from Iran and with whom she has been friends for a long time. When they happened to be room-mates in a hotel during a visit to the Impuls Festival in Graz in 2019 and spent a lot of time together, they realised how similar their musical approach was and how fruitful their discussions about concerts and music turned out to be. Hence the idea of composing together, which led to their very first common project, a draft for a call for proposals by the Neuköllner Oper Berlin for a chamber opera, which had an astonishing impact: “At first we only had a small idea, but in three weeks we had a finished concept, including lighting and stage design.” Even though the draft was not accepted, a first step had been taken.

Honesty as precondition

With their draft for a realisation of Albert Camus’s The Stranger, in which philosopher Johannes Abel joined their planning team, they won second prize in another composition competition. While their joint composition ps: and the trees will ask the wind for double bass, Paetzold flute, violin, objects, audio and video – in which they artistically processed Iran’s socio-political events – was premiered at Bludenzer Tage für zeitgemäße Musik in 2021.

“We eventually found a way to be just as critical of each other as we are of ourselves. Our common work is based on honesty, which can sometimes lead to difficulties, but if we disagree, we keep going until we are both satisfied and in the end, we come up with a much better solution.”

In Die Zeiten – Versuch (über das Paradies) for baritone and piano, premiered at the Lucerne Festival in August 2023, Elnaz Seyedi wrote the music to a text by Iranian poet Ahmad Shamlou.

Working in new places

Elnaz Seyedi also draws inspiration from the various location she gets to visit during her travels. That’s why she is particularly fond of residency scholarships. The composer believes that getting away from everyday life allows you to suddenly recognise the beauty of the familiar that would otherwise remain buried in the daily routine – a thought that she incorporated into Postkarte (Moorlandschaft mit Regenbogen) , which was composed for the Ensemble S201 from Essen in 2016. In 2020, a residency scholarship from the Bartels Fondation took her to Basel’s Kleiner Markgräflerhof, while in 2021 she spent a few months at the Künstlerhof Schreyahn in Lower Saxony, she was amazed at how productive she had been there.

Her orchestral piece A Mark of your breath was inspired by her stay at Künstlerhaus Schreyahn – above all by the vastness of the sky and the landscape in Wendland.

‘Dunst’ – world premiere in Donaueschingen 2023

This autumn, Elnaz Seyedi is once again working at a different location thanks to a residency at Künstlerhaus Otte in Eckernförde, where she can bring her work to the local audience through concerts as well as film evenings. She also just completed “Dunst – als käme alles zurück”. For the concert programme Echoräume by ensemble Ascolta at this year’s Donaueschingen Music Festival, two artistic tandems consisting of a composer and a writer have formed and – with complete freedom in their approach – each one of them developed a joint work. The piece by Elnaz Seyedi and author Anja Kampmann for two voices and ensemble is about the aesthetics of the fragment and the transition between language and music…

…and who knows what compositional ideas Elnaz Seyedi’s stay in the town on the Baltic Sea will generate.

Friederike Kenneweg

Premiere Donaueschinger Musiktage: Saturday, October 21,2023 at 11:00, Mozart-Saal DonaueschingenEchoräume with Ensemble Ascolta: Elnaz Seyedi and Anja Kampmann Dunst – als käme alles zurück; Iris ter Schiphorst and Felicitas Hoppe: Was wird hier eigentlich gespielt?

Elnaz Seyedi, Donaueschinger Musiktage 2023, Ensemble Ascolta, Younghi Pagh-Paan, Caspar Johannes Walter, Hochschule für Musik Basel, Anja Kampmann, Ehsan Khatebi, Vanessa Porter, Ensemble S201, Neuköllner Oper, Künstlerhaus Otte Eckernförde, Künstlerhof Schreyahn, Bludenzer Tage für zeitgemäße Musik, Lucerne Festival, Impulsfestival Graz, Bartels Fondation

Sendung SRF 2 Kultur:

Musik unserer Zeit, 2.6.2021: Nach neuen Meeren – die Komponistin Elnaz Seyedi, Redaktion Cécile Olshausen

neo-profiles:

Elnaz Seyedi, Donaueschinger Musiktage, Lucerne Festival Contemporary Orchestra